Cleaned up some, but still really boring, and very nearly pointless. (It has an alternate purpose, can you guess it?) You were warned.--K

My wife has been reading Thomas Sowell's pile of assumptions and hearsay about economics and politics (frustrating but forgivable, I started from similar places as I grew interested in the world around me). The information in the book has already led to a spousal, um, spirited discussion, spurred by the Massachusetts gubernatorial debate last week, as the crooks and loons had at the subject of health care.* Sowell offers up the usual conservative bromides against state-sponsored medical programs: people will use services more freely when it's paid by someone else. He also argues, I think contrary to his first point, that R&D isn't supported in state-run systems like Canada's. (This is bullshit, right? If more people are using services, isn't there more money invested into the medical economy?). And of course he rails against malpractice insurance, even though it's a tool to make the system equitable.

As is usual for any think-tank pundit, he's telling only a small part of the story. The government may well have no business planning** the ins and outs of the medical industry, but no one's asking that. State systems instead seek to run the medical insurance industry. Since insurance depends on spreading risks, then it makes sense to spread it to the largest possible pool, namely the entire public. A self-selected pool of people of similar risk is an OK as an economic exercise, but it neglects the social goals of insurance. Some of the economic goals too--you still might catch the flu from a poor person (or smallpox, polio, etc., depending on how "free market" you want to get).

Is state insurance going to break the bank? As I see it, the costs of health care are broadly distributed as follows:

- Services

- preventative (including disease control)

- emergency

- Development

- Administrative

- point of care

- insurance

- legal

In America, it's usually argued that costs are dominated by development, which is driven by our collective desire to have a medical industry here in the states. This desire is independent of the manner of payment. Administrative costs are another biggie, and I understand that paper-shuffling and Byzantine payment documentation outweighs the legal fees by a big margin (but again I can be convinced otherwise). I've never been sold that emergency costs outweigh preventative costs in the aggregate. Prevention is cheaper case-by-case but you need more of it. Prevention does lead to a better quality of life, however, as does having as many mechanisms as possible to correct system defects.

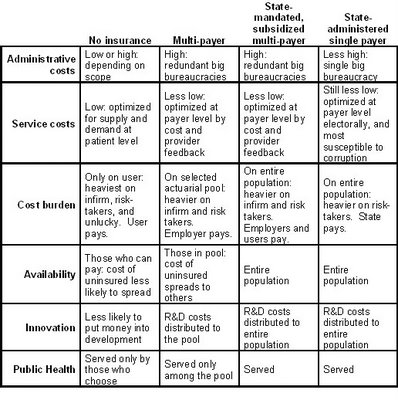

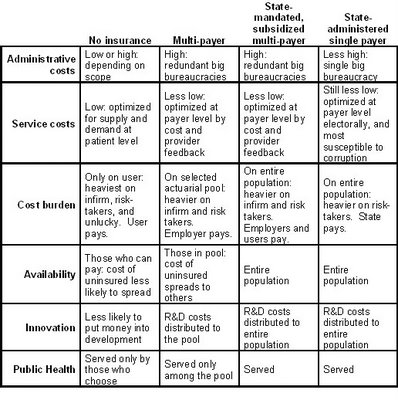

But back to the debate, as well as my familial argument: what's the best health insurance model? I've considered four possibilities: (1) no insurance; (2) optional multi-payer insurance (the prevalent model in the U.S.); (3) mandated multi-payer insurance (the new Massachusetts model); and (4) state-administered single payer insurance (as in Canada and Western Europe). They're arranged on the following table, and I make my judgements below.

Non-insurance model:

Non-insurance model:This is the real free market case, and even though some libertarians prefer to imagine the "country doctor" scenario, in which small independent medical businesses compete locally for my health care dollars, it's more likely that doctors and hospitals would consolidate corporate-style. (The idea of the heart surgery division of McDonald's is dark comedy.) These medical service divisions will still be sensitive to supply and demand, but accountable to shareholders. And it's probably a myth to think this would eliminate very much bureaucracy.

There would be no spread of the risks in this fantasy model. If the wheel stops on you, then hopefully you've saved up. If you're young and healthy, pay up. If you're old, hope for a quick death. Even though it's an economic issue in many ways, you can forget about public health too. No one's going to suggest that your neighbor gets his shots.

I think Sowell's wrong that this fantasy situation will stimulate much R&D however. That's because price minimization fights R&D and infrastructure development. Yes you still want to please your shareholders with growth of new technology (or markets), but

the R&D required for corporate growth is less than the R&D demanded by altruistic public goals. That's the problem with the drug industry. That's why corporate R&D in general has slowed so damn much in this country in the last century. Meanwhile, advances will come in areas that people can demand in advance, like plastic surgery, and highly marketed boutique ailments, while basic care maintains bare minimum standards. (This is why there's a shortage of flu vaccine. No money in it.)

Insurance models: The multi-payer system is basically the current U.S. system--it's admittedly the most expensive on the market. We're pooling risks, but only among select members of the public. We've introduced some measure of centralized planning (less responsive to cost pressures) and a whole raft of paperwork (more expensive). An HMO is going to feel some measure of pressure to reduce costs, but they're far removed from users. It's the worst case of all administration-wise because there are multiple payers for the same care, and these must be sorted and stacked by care providers.

Doesn't the multi-payer system encourage competition between insurers? Only if there's really much of a choice. There are few options for individuals, and employers quickly find that the providers are all damn similar. Furthermore, a diversity of plans shifts costs (on a statistical, not an individual, basis) to the sicker and more risk-prone. I'd prefer that the people engaging in risky behavior paid more, but people who are born that way? Or who were unfortunate enough to get old? Hardly seems fair.

In any of the insurance models, more money is flowing into the system for basic care (and therefore more money overall), because more people are utilizing it, such is Sowell's "free" argument. This distributes the costs of R&D as well as for care. The more inclusive plans distribute the costs wider, and presumably generate more capital overall for this sort of thing.

The optional multi-payer model shifts the costs of the uninsured to people who do pay. The uninsured end up getting treated anyway, and since the costs are distributed, people don't complain so much about absorbing them. The uninsured likewise fall out of the public health net. The state-mandated or -supplied models plug these holes.

The difference between state-mandated insurance and state-provided insurance is that there is less redundant bureacracy in the latter, reducing costs, but the administration is more centralized. I don't think there's much difference in managing the care of 30 million vs. 300 million users, but the effects of corruption or mismanagement would be more damaging, and could only be fixed by state mechanisms--courts or legisltation. And you're as likely to find a well-informed voter as a well informed consumer.

Finally, I want to note that state-backed plans remove the burden of insurance from employers, and instead distribute it among citizens. The same pot, maybe, but it offers corporations more competitive advantage when it comes to dealing with companies overseas, which, as it turns out, typically

don't supply insurance to their employees. Tying insurance to employment seems to mung up both enterprises.

*I'll probably vote for the loon.

**if you read the earlier draft, I'd written "regulating," which was not what I meant. I'm all for having, for example, FDA approvals.

Mr. Smug here on the left was taken about six months before Chubsy McFatass up above. It was before peak poundage, but believe you me, that's a purposeful pose, and there's a reason for the beard. It guides the eye to a then-hypothetical jawline. I don't know about you, but I'm sick of looking at his scruffy mug.

Mr. Smug here on the left was taken about six months before Chubsy McFatass up above. It was before peak poundage, but believe you me, that's a purposeful pose, and there's a reason for the beard. It guides the eye to a then-hypothetical jawline. I don't know about you, but I'm sick of looking at his scruffy mug. Still, I don't consider the cameo anything like a success. Maybe if I could airbrush in some more hair and learn how to smile. In an effort to look less like a total dork when I reply to people, I'm going with Mr. Stick Figure as my new profile shot. If you can't get enough of looking at me, I encourage you to bookmark this post. (Otherwise I'll send you the shirtless photos for $5.95. Good for darts, drink coasters, scaring children, etc.)

Still, I don't consider the cameo anything like a success. Maybe if I could airbrush in some more hair and learn how to smile. In an effort to look less like a total dork when I reply to people, I'm going with Mr. Stick Figure as my new profile shot. If you can't get enough of looking at me, I encourage you to bookmark this post. (Otherwise I'll send you the shirtless photos for $5.95. Good for darts, drink coasters, scaring children, etc.)