Review of Our Kind by Marvin Harris

[note, if anyone read the first draft of this...I'm sorry.]

So much of history, as it's usually presented, is either a local microcosm or a culturally specific snapshot, it fails to capture the big (the big impersonal) picture of the human experience. Philosophy follows a similar flaw of intimacy, driving for a first-principals explanation of the human condition, proceeding from axioms created in our skulls to as many future conditional progressive tenses as may be (here's how I think I think, therefore, here's how society should work). I am liking the empirical perspective lately, that is, the anthropological one, observing the evidence of human coexistence and making inductive generalizations from the pattern of the data. It's been my growing conviction that for all the myriad ways we're fucked up on an individual level, human behavior in the aggregate is a lot more predictable and explainable than six billion partisans would have you believe.

In Our Kind, Marvin Harris moves quickly to an important distinction in this explanation, in truth another one I've been wrestling with: that cultural evolution is different than the biological sort, faster, and even if it's not working through genetics, it's force is similarly powerful. Harris describes how cultural development as an unconscious, collective means to most efficiently realize our various biological imperatives. The species is, more or less, equally endowed, but we react in different ways to the externalities of different communities: different availabilty of proteins, vitamins, and heat sources, differnt population density, different history, and varying degrees of feasibility that somewhere else exists to go. The outlines of politics and culture derive from these parameters. He puts the lie to fertility as a biological imperative, digging up anthropological evidence and biological analogies to show that humans are more wired more for sex than we are for babies, and develops the consequences. He pokes at race as an artifical construct. Our body shapes and colors over the generations correlate more to local geography than our ethnic heritage, both because of cultural selection and extensive interbreeding (Jews, he notes in an example, generally look more like the locals than they do Jews elsewhere, which is maybe one hint that journalists should be careful not to casually conflate ethnography with genomes.)

It gets touchy in parts. Harris outlines ways in which early societies dealt with population pressures, reducing the idea of war to a means to deal with this, and correlating that with misogyny. Preservation of a warrior class limits population more than in the obvious way, Harris says, and includes selection for male heirs for the patriarchy, pushing toward female infanticide as a remarkably common device, even in modern times. Historically, life has officially begun at the point parents decided to keep the child, sometimes months ex utero. He questions the cost of misogyny in terms of male life expectancy (along with the contemporary unwillingness to question this), paints government as an inevitable consequence of animal domestication.

I don't think any of the above discussions are comfortable, but the cases are strong. His religious angle is perhaps the most sensitive. He describes "killing" religions, entailing animal and human sacrifice, as a development of a means of protein redistribution, drawing patterns across the globe from Aztecs to the Vedic to the Pacific island traditions. The non-killing faiths he paints as reactionary creeds developed to address the failure of the faiths that passed out meat, usually in response to specific political pressures. He draws a line from here directly to subjugation empire, implicating the gentler religions as a direct enabler of military powers. Why? Because making a virtue of poverty and delaying material rewards past death suits would-be emperors brilliantly. The first act of conquest of non-killers, cites Harris, is to convert to the non-killing faith, as true of Christianity, as of Jainism, as of Buddhism. The proscription against killing, historically, has been easy enough to circumvent, but the faith in ethereal rewards much harder to shake, and murderous zealots have been useful tools of tyrants. (One amusing point: even as Harris constructs a general condemnation of religioun that quite clearly includes the Pauline faiths, he sticks with the western conceit of weighting Biblical history toward the factual, using Christian-formal terms like 'year of Our Lord', and citing that holy book, and only that one, using chapter and verse. It's got to be force of habit.)

Stylistically, Marvin Harris both worked for me and didn't. His ultra-short sections--the book is five hundred pages long, but every third page was a blank title--got right to the point, but they were so brief and un-footnoted, that it lent to a less than scholarly feel. It's not that the sections are unresearched: the author has done his share of influential work the field himself, and there is a a detailed bibliography for each tiny chapter in the back. He just doesn't point to it. He also has a penchant for scribbling over his weaker points with anecdote or irritable analogy. For example, he's probably out to lunch on his message of gender identity--not so culturally controlled between sexes as all that--but on the other hand, his message that cultural selection usually satisfies the biological preferences in the aggregate is almost certainly true, and biologically, he's largely divorced sexuality from both reproduction and gender anyway. I admit that I'd be more bothered by his idiosyncratic style if I agreed with less of it.

We all know how short the timeframe of civilization is compared the earth's history, but even our species is young, only around for a hundred thousand years or so. By contrast, our various hominid ancestors populated the earth for about 3 million years. (Our most recent evolutionary analog, the Neandertals were a short-lived species, only lasting about 200 thousand altogether). Even given the age of our genome, sapient, language-using humans have only been evidenced for a fraction of that, about 35,000 years. I can't accept that early humans were any differently intellectually gifted (and neither can Harris, which is why he describes evolution in the cultural sphere). In that short time, we've graduated from the stone tools that our ape-plus ancestors and cousins had used, and covered the earth in dense societies, razing mountains and forests, and erecting countless evidence that we lived. Although we may still fight like animals, we've made a hell of a mark in the short time our kind has been civilizing.

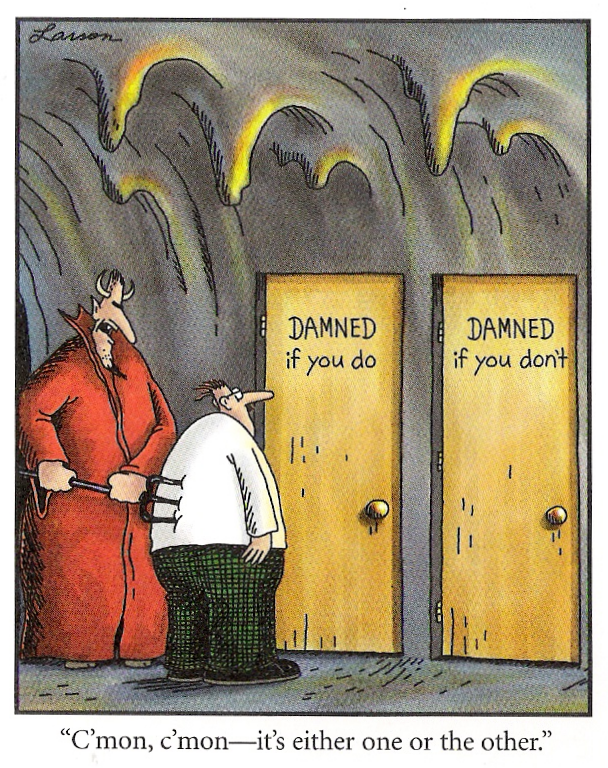

And the big question remains this: are we going somewhere, or have we achieved our ecological niche? According to ideas of punctuated equilibrium, species persist for a long damn time, but originate and fill in their ecological space very quickly. In terms of biological evolution, the fossil record and all that, 35 kiloyears ain't much. We humans are probably still spreading into our role As a conclusion, Harris calls our penchant for empire and evil as the likely inevitable cultural consequences of our nature. Our failures to will into being benevolent governments are a result of the unfortunate statistical average of human action. They've all followed similar paths. Is there hope, he wonders, a conclusion beyond the state? I have to think that there's not going to be any success in regressing pre-state, that the factors that pushed governments into existence--food dependence, population, and circumscription--seem to only drive one way. But here's the thing, the catch: trying to will cultural evolution forward is how our biological imperative works, and there may be a point we haven't yet achieved with it. We're certainly on different ground this time in terms of communication, size, and boundaries. Is there still time to realize a better existence than empire?

I'm not very optimistic actually--existential brinkmanship can't continue forever--but the idea of a better future beyond nation-staes is the hope I can find. Maybe we'll get there.

who can safely be called the most famous holder of the surname. He was a minister and writer who came to the radical conclusion in the nineteenth century that there was no moral excuse to offer blacks and women anything less than full equality and opportunity in society. He put these beliefs to test, leading an (otherwise) all-black regiment in the Civil War, and preaching and publishing and corresponding in impressive volume. He's probably most well known for discovering and publishing Emily Dickinson. We're almost certainly unrelated, but if I had a son, I'd have lobbied to call him Tom, and certainly not after the pop star.

who can safely be called the most famous holder of the surname. He was a minister and writer who came to the radical conclusion in the nineteenth century that there was no moral excuse to offer blacks and women anything less than full equality and opportunity in society. He put these beliefs to test, leading an (otherwise) all-black regiment in the Civil War, and preaching and publishing and corresponding in impressive volume. He's probably most well known for discovering and publishing Emily Dickinson. We're almost certainly unrelated, but if I had a son, I'd have lobbied to call him Tom, and certainly not after the pop star.