It's anecdote time, everyone!

At the end of October, my grandmother proved, despite the growing evidence, the limits of her resilience. She'd shown an impressive constitution for an old lady. In her eighties, a little less than ten years ago, she broke her hip, and within a year, recovered from it. A handful of years after that, she moved from her own house in Florida to be closer to family, opting for a new life in an assisted living facility. It's not the worst arrangement for someone who is used to independence: basically it's an apartment of your own that comes with a red phone to care facilities, a common meal a day, and someone who is paid to notice if you don't show up for it. She'd been increasingly unsteady on her feet however, and five or six months ago, she fell once more, and this time broke her pelvis. At 92 years old, it really fucked her up, not just laying her flat, but taking an exceptional mental toll as well. Confusion and depression isn't something you want to see in someone in that state. I got sad emails from my mom and my aunt, fearing it was the end, but she dug in and started pulling around from this injury too. She moved in with her daughter, and when I saw her in August, she was confined to a wheelchair, showing her age, but nearly herself, despite everything. Unfortunately, a bacterial infection took root at some point in her stomach and progressed unknown on the inside for a while, and when she was rushed to the hospital intravenous antibiotics at least drove out the bugs. Amazingly, she appeared to be recovering from this too, but the 93-year-old body only had so much of a rally left in it.

[The point is that she needed care, but still had a lot of life going on. I don't want to neglect to say how great a person she was, and I miss her a lot. She was a woman who liked pretty much everyone she came across, enjoying the conversation and company, not generally thinking to notice people's flaws and issues. She had friends wherever she went, and it wasn't so much that she was sweet and nice, although she was very nice, but she wasn't about drama. My cousin said at her funeral that she was cool without having the slightest notion that she was cool. She was someone who made decency look effortless.]

Her care was financed mostly by the investments that my grandfather had put together over the years. (I think that he would have been happy to know that these did indeed provide over all that time.) Caring for her pretty much wound down the whole shebang though, including the house the old man had built with his own hands. They don't keep me in the loop with all the details, but I understand it came extremely close to breaking even. The state may have picked up a few bucks right at the end.

On the other side of the family, years before, my father's mother's odd behavior after her husband's death turned out not to be, as 25-year-old Keifus would have preferred to believe, the natural product of solitude and her own quirkiness, but rather the early stages of Alzheimer's, and it slowly worsened over a period of years. She lived by herself, with lots of visits from her children, for as long as she was capable of doing that, and afterwards moved to a nursing home when she was not so capable. I wasn't around all that much at the time (winding up grad school, moving to the DC area), but I still failed to take many of the opportunities to visit that I did have. I feel terrible about this. It may well be one of the three or four clinging regrets that I rave about when it's my turn for my mind to disintegrate. It deserves to be.

She was my family's first encounter with long-term medical finances, and, on top of watching someone's warmth and wit dissolve, I remember that it was pretty damn wrenching to have to work the system. These grandparents were also frugal (a more throwback Yankee sort of frugality), but it didn't take long at all to burn through all their assets, and after that it was years of government assistance to maintain that modest level of care.

[Both of my grandfathers, if you were wondering, were done in by prostate cancer and predeceased their wives. They'd both received hospitalization and some home care. I don't know how it was taken care of financially.]

Here's some final anecdata, what's actually driving the post. There's been a health scare from my wife's side of the family this month too, from someone not so old. Complications from routine surgery led to weeks in the ICU (a close thing, but now recovering, thanks). A completely different set of finances there (veterans and state retirement benefits), but my wife came back with tales from the waiting room of the humiliating dissolution of wealth and dignity that everyone else was dealing with as their loved ones were making the transition to state aid to cover their massive medical burden.

It's not in most of our characters to put our elders on the nearest ice floe at the first signs of impairment. We'd rather, if possible, that they decline with comfort and dignity: because we owe them, because we love them, because we'd like to limit the pain and humiliation for ourselves too when it's our turn. Because they're still human beings dammit. And if that's insufficiently cynical, then remember that the senior care industry only grows, and there's more than adequate economic motivation for the governors to allow it continue to hoover our last dimes.

In Weldon's last post, he had a line that got me. The context was different, but the point the same: A lot of people won’t get help before they’ve lost everything.

Long-term care was part of the Medicare discussion when it was drafted, but that didn't really survive into the ultimate legislation. Medicare is more designed for hospitalization and any coverage for convalescence is meant in the context of recovery from an acute illness or injury, and it only will cover limited care in this regard (a little over 3 months is all, by specialized providers, following at least 3 required days of hospitalization). Non-specialist care in an assisted living center or in a nursing home (I am not what proportion, although this is no doubt depressing too) is provided for the "medically needy" through the Medicaid program, the specific requirements and benefits of which vary by state. We all know about Medicaid for the unwashed poor, and our cracker classes are plenty indignant about that idea of course, but it's a good chance that even your typical pasty boomer, if those that hang on long enough, is going to wind up there, just like their parents did. You typically becomes medically needy by spending all of your liquid assets and all of your income on medical care. It's not a euphemism, it's actually a requirement: you have to spend everything you own before they will give you a nickel. If you were wily enough to see this coming and started giving it away, then (within three years) that's illegal too. In 2004, 56% of nursing home expenditures were provided by Medicaid, a good measure, I suspect, of how long people currently outlive that 100 days, or their fortunes.

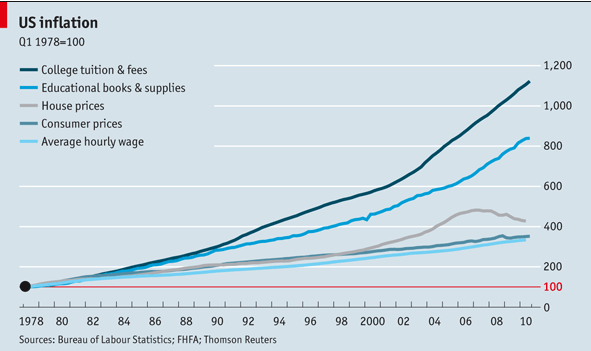

The budget alarmists are afraid of escalating trends in medical costs, and for long-term care of the aged, and no doubt they should be. Unfortunately, the policy argument to address this tends to be between people who want to provide some level of care without using the word "Socialism" and without threatening the precious health industry with regulation, and people who flat out don't want to provide it at all. In the CBO report linked above, the prescription that it advocates, or the question it begs, is private long-term care insurance. (I realize this is Bush-era stuff, but (a) it's the damn CBO, and (b) the spectre of entitlement reform hasn't exactly disappeared with the Harvard cowboy.) After presenting its data and offering the correct observation that people are not incentivized to accumulate extra savings when the price of keeping them in pudding and rough-handed orderlies in their waning days corresponds exactly to how much they got, it then concludes that Medicaid benefits should be cut, that whatever few breaks still exist should be quickly removed in order to provide more tough-love incentives to save or buy private insurance. This is good evidence of why you should never mistake establishment-friendly economists for human beings. I mean, what the fuck else is Medicaid going to take away from you? And an automatic impoverishment in the last phase of your life is only one reason to avoid savings, but let's not pretend it's the only one: zippo return on reasonably secure vehicles, a bigger take of your life for homes and educations, and 40 years of increased credit instead of increased wages. Fuck you, the CBO.

But it'd surely be worse if we lost Medicaid, wouldn't it? For the people, yes, but more important than that, we're talking money that people are willing to pay, and that always has a voice. The way I see it, there is a constituency that stands to get rich off of expensive care (medical providers), and one that stands to get rich off of expensive administration of it (medical insurers). A push toward private long-term care insurance may be more expensive and less efficient for the people (assuming it follows other kinds of health care), but it's a win win for the favored sons.

My grandfather was a smart and resourceful guy. He got his P.E. in middle age without any of the usual college attainment and changed his career path. (I'm sincerely impressed with this--I keep some of his old-school slide rules and drafting tools to remind me what a sorry excuse for an engineer I turned out to be by comparison). He managed his savings as shrewdly as anyone who has something to manage, but who is not by any means a player, can. (That's a compliment too, but now intended a little backhandedly--having something to manage is an important part of that equation.) I didn't realize that he had help building it up in the first place with a surprise inheritance from one of his uncles. There are fewer men that are self-made than have improved their forward trajectory, but certainly either one is hard enough. The thing is, those sorts of windfalls don't float around in quite the same way as they used to, not for us little people. Too expensive to get old.

Who makes it out these days without experiencing a steady decline? I personally think it's worth it for general humanist principles that we extend quality of life as best we can, and although it's a shitty answer, Medicaid, savings and long-term care insurance are at least answers. We are priveleged to have some forward social trajectory, but inheritance is not really part of it for the middle classes these days, and we should probably count ourselves lucky that the expense is for now avoided between generations and between spouses, and that there's still a chance of keeping the house. But let's be honest here: the system as constructed is designed to consume a modest estate. This is is what happens to the net worth of the non-rich. I don't like inheritance as the mechanism to keep people less than poor, but forced liquidation on the low end adds to inequality. The next priveleged fucker who starts whining about the estate tax deserves to get hit with a bat.